It intrigues me that in a a world where the entire process is digital, there’s still intrinsic value to be had from a distinctly analog concept; the concept of prints.

Film is so unique in that traditionally, people have just made prints directly from their negatives or slides. But then the digital revolution happened, and people started digitising their negatives so they could view them on their new-fangled computers. Prints kinda, sorta, fell out of fashion as costs for developing and printing soared with the digital revolution. For many people, digital was all about convenience — being able to instantly view photos and share them to others was a huge plus. Having to wait an entire hour before photos could be viewed was a thing of the past. Our time grew more valuable, and film was all but forgotten.

Not so in the film industry, apparently, where film still holds a special something over digital:

No wonder, then, that directors like Christopher Nolan worry that if 35mm film dies, so will the gold standard of how movies are made. Film cameras require reloading every 10 minutes. They teach discipline. Digital cameras can shoot far longer, much to the dismay of actors like Robert Downey Jr. — who, rumor has it, protests by leaving bottles of urine on set.

There’s something about film which makes it command a certain amount of respect, a certain reverence. Digital is cheap. Film is not:

“Because when you hear the camera whirring, you know that money is going through it,” Wright says. “There’s a respectfulness that comes when you’re burning up film.”

I do quite a bit of shooting for my youth group, and while I’m definitely getting too old for a “youth group”, no one really seems to mind, or at least they’re not telling me about it (a topic for another time).

At youth, we have this wall that shows off photos of the youth. Photos from past events, photos from trips to Planetshakers, photos from previous Relay events, and things like that. It’s pretty cool, but the photos are a few years old now.

I was recently approached by the youth leader, to see if we could put a few new photos up. As I was the one who had been taking photos for the better part of the year, I was the one who would provide the photos. It made complete sense, and yet, to be asked of such a thing felt like a huge honour. I know it was probably inevitable and just common sense, but still, this was a Pretty Big Deal for me.

I had already uploaded a few photos to our Facebook group, and I already have a collection in Lightroom that has all the best shots from youth, so choosing which shots to print was a non-issue.

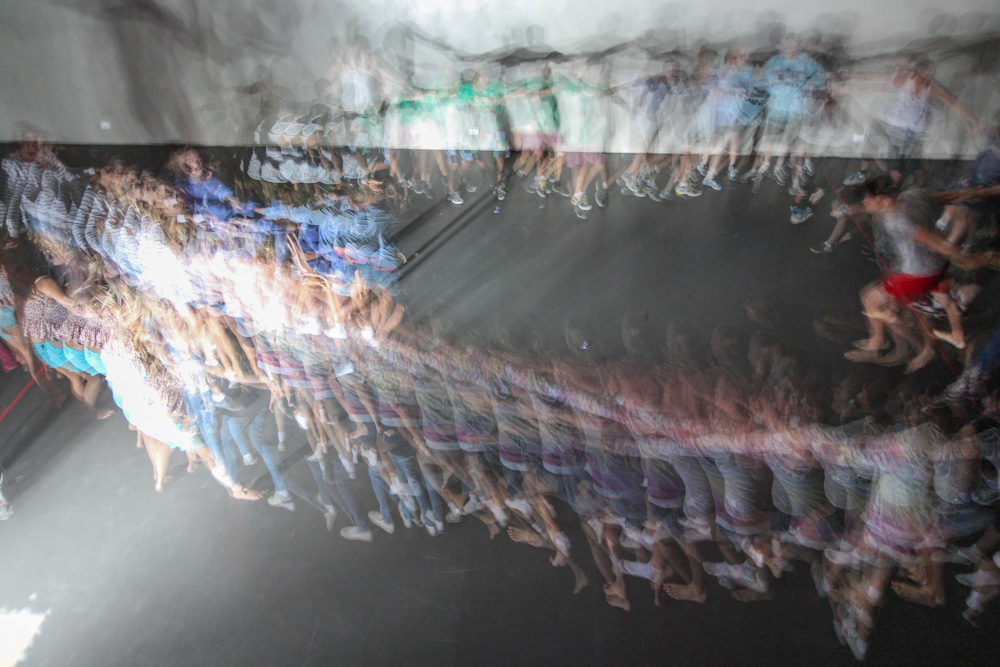

Numbers kind of were, but I ended up being ruthless and culling mediocre photos from the ones that were worthy of being printed. There were a few exceptions to this rule, and they were mostly photos that were good in terms of subject/composition/emotion, but perhaps technically flawed (slightly missed focus, limbs cut off weirdly, etc). It was interesting finding a line between choosing photos that were interesting and showed the “right stuff”, and photos that were perhaps not that good in terms of subject, but were still interesting, like the photo below. One night we played with a strobe, and that made for a cool photo, even though you can’t make out anyone in particular.

Anyway. 105 photos later, with about 7 enlargements of the group shots, and I’m happy with how the photos turned out. It was interesting seeing the difference between how the photos looked on-screen and how they looked when printed out, but for the most part things were pretty good.

All in all, a good experience. It’s kinda funny, because photography enthusiasts and hobbyists don’t really print out their digital images all that often, but mums, dads, and grandparents do it all the time.

Funny how things work like that.