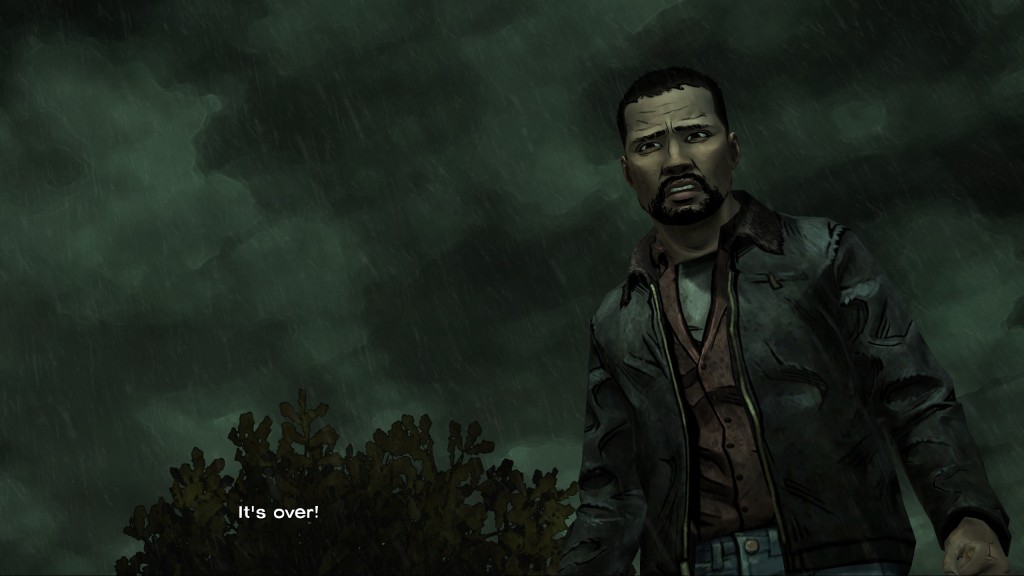

Spectacular cell-shaded scenery, when you’re not being mobbed by the undead.

Look, I’m not kidding around here. If you’re at all serious about games, or watch and enjoy the TV series by the same name, you should play The Walking Dead on whatever platform you feel most comfortable with.

The Walking Dead isn’t my first interactive adventure from Telltale Games. That honour has been bestowed to a smaller game called Puzzle Agent, which is kinda similar in a lot of ways — there isn’t such a focus on puzzle mechanics like there is in Puzzle Agent, but you do get the same explorative, story-driven gameplay, accompanied by a healthy dose of dialog trees.

Telltale Games are quickly becoming the masters of the interactive adventure genre on multiple platforms, and for good reason: most of the story-based games they make are of a very high standard.

For those that aren’t in the loop about The Walking Dead the game, but are a little familiar with the TV series (and possibly even the comic), you’ll be pleased to know The Walking Dead follows the same storyline as the TV series.

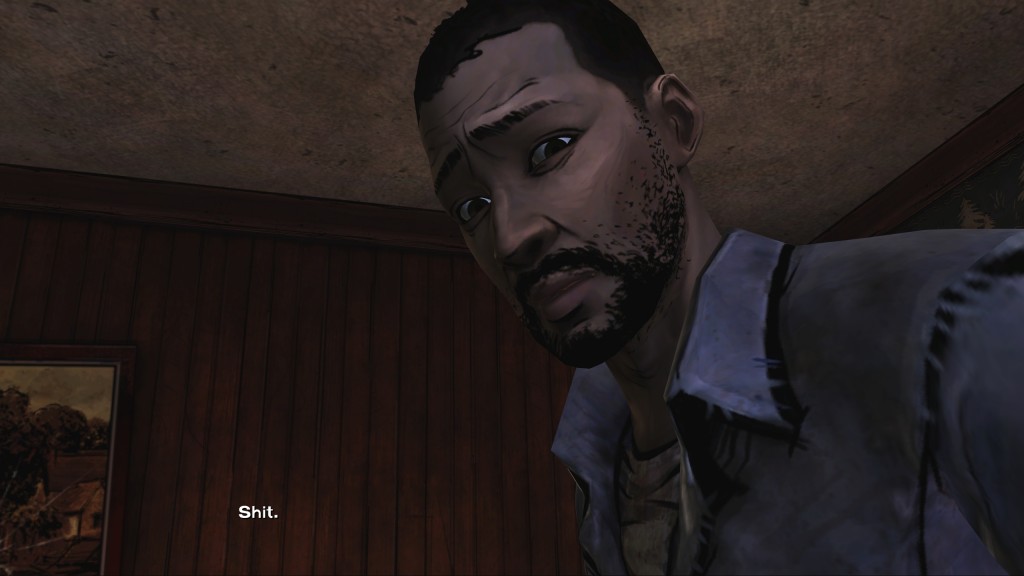

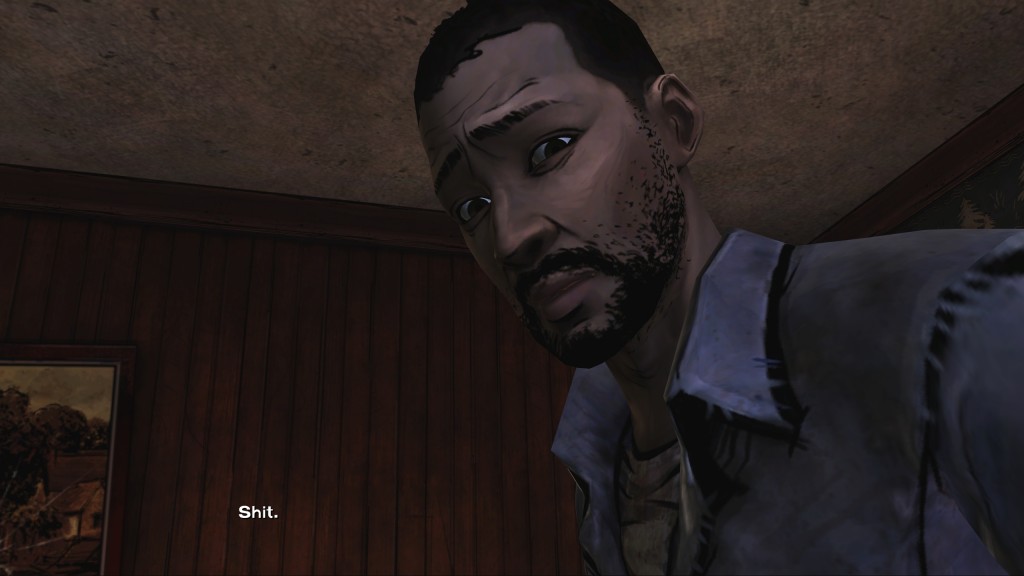

The Walking Dead‘s lead character is Lee Everett, a guy who’s on his way to prison when the cop car that’s he’s getting a ride in hits a zombie, and from there, all hell breaks loose. At first he’s confused about what just happened, and why he’s just had to shoot the cop that was taking a ride with, and then he starts to understand that there’s something very, very wrong about the world he’s woken up in.

Which is actually one of the best things about The Walking Dead; there’s real, believable characters. Just like the TV series, you soon meet up with a group of fellow survivors who seem alright, and you quickly form relationships with them. There’s hard-ass Kenny who’s just looking out for his son and wife, there’s can’t-work-out-batteries Carley, the reporter who’s actually a dead-eye with a pistol, and there’s even a few military types who take charge of the group and make the decisions (but ultimately, you make the call).

But the game wouldn’t be complete without some kind of purpose outside of simply surviving the zombie apocalypse, and in The Walking Dead, your purpose is Clementine. She’s one of the first characters you meet in the series, and by that time, she’s already been surviving on her own for a few days. You decide to take her under your wing, and that’s that: the status of her parents is a little murky, and essentially, she’s the little impressionable girl that looks up to you — even though you’re not her real dad, you’re just a guy/some neighbour/silence.

That’s pretty much how the first episode starts. The Walking Dead is released as episodic content: as of writing, three out of five planned episodes are currently out on PC and Mac. They’re released about a month apart, and each episode is around two to three hours long.

Clementine is all you have.

Which brings me to another thing that’s great about The Walking Dead: whilst it’s a game that’s meant to played episode by episode (sometimes, as in the case of episode one and two, with months and months of in-game time in-between), it’s s tailored experience all the way. Make no mistake: the decisions you make in The Walking Dead could have implications two seconds later, thirty seconds later, a few minutes later, even an hour later, and in some cases, even a few episodes later. In The Walking Dead, the choices you make count for something, even if it’s not immediately clear what that something may be. Perhaps that lie you’re about to tell will destroy an already-fragile relationship with another character, perhaps it won’t. The fact is, you won’t know until you make that call.

And boy, do you call all the difficult shots. One of the best reasons you should be playing The Walking Dead is because of the decisions you’ll make along the way; The Walking Dead is all about morals and tough choices, with a little accountability and perhaps even regret thrown in on the side. One of the best things about Telltale’s interpretation of the story genre is the little details, such as when you’ve been particularly hard on a fellow survivor, and it says something like “Kenny won’t forget your words”. It’s a unnerving feeling to know everything you say and do is being judged by other characters. Maybe you choose to tell the others what you were doing when the world ended, or maybe you make something up. Either way, whatever you say will have a profound impact on how the characters see you. Again — maybe that will matter down the track, maybe it won’t.

One thing I love about the dialog in The Walking Dead is how silence is also a valid response. If someone asks you a question you don’t like, or can’t choose from the various options in time, then you simply stay silent. If it’s a particularly polarising decision, silence then represents the fence-sitting option; other times, another character might be asking you about your past: if you say nothing, then that might be seen as guilt or something else. It’s a great game mechanic that works really, really well.

Let’s get one thing straight, though: The Walking Dead isn’t a twitchy first-person shooter like seemingly every other zombie apocalypse game out there. No, it’s a point-and-click, interactive adventure game, and that means you’ll be doing a little puzzle-solving here and there, (how to distract those zombies whilst I run over here and grab these keys?), interacting and exploring your current environment, and talking to other characters via dialog trees. About as twitchy as it gets is the quick time events (of which there are a few, but they’re do what they’re designed to do, i.e. get you through a panicky moment without some uber-complex keystrokes), which don’t really count. There’s one scene where you’re shooting zombies with a rifle, and it’s laughably easy to get kills: you pretty much just point the rifle in the direction of the zombie (you have a scope to make this easier, for some reason), and you click the mouse, and boom, headshot.

Lee Everett — Tough Decisions

I’ve been putting a few hours into DayZ recently, and it’s interesting drawing parallels between that game and The Walking Dead. They’re both about zombie apocalypses, and as much as they’re both totally different games in some respects, it’s strange how some things are similar. In one episode a fellow survivor is about to shoot a bird, but you tell him not to because the noise will draw the walkers — things like “noise attracts zombies”, things like that that you learn in DayZ, and can now be applied to The Walking Dead. In some ways, playing DayZ prepares you for a lot of what was going to happen in The Walking Dead: you’ve been there, done that, so some things are easier. But then some things, like making those black-and-white decisions you have to, just aren’t easier no matter which games you’ve played before this.

Spec Ops: The Line is another recent game that I enjoyed quite a bit, and in many respects, it’s actually more similar to The Walking Dead than DayZ. But where Spec Ops has an entire game which meanders through various twists and turns leading up to one of the best finales of any game I’ve played, and where Spec Ops builds up the entire game to finish in a spectacular fashion, The Walking Dead is a lot more episodic. You take things as they come, knowing that things might change for the better (or for the worse) in later episodes. The episodic delivery suits it well, I think.

As much as I enjoy pretty much every gameplay and story aspect of The Walking Dead, there are a few things that mar an otherwise brilliant experience.

Let’s start with the black and white decisions you’re forced into. At certain stages, you’re forced to make a critical decision between two absolutes. That whole “infinite shades of grey” thing you hear about? There is a little of that in a few of the longer-term dialog options you get presented with, but the critical events, those are entirely black and white. I don’t want to spoil things too much, but you’ll be choosing the lesser of two evils a little more frequently that I’m comfortable with. I don’t really have a problem with that, but the fact that you’re forced into them is somewhat harsh.

And while we’re on the topic, for a game that’s all about the freedom of choice, sometimes, you don’t get any. That is, you can make decisions along the way, but being a game that has finite possibilities and doesn’t account for every possible outcome from the hundreds of dialog options and choices you can make, there’s only so many possibilities that can actually happen. Maybe you want to run off with a mildly attractive, slightly-insane, military woman, but that’s not how it’s meant to play out. It’s the illusion of choice, and once you realise it’s very real, it kind-of spoils the game. A little.

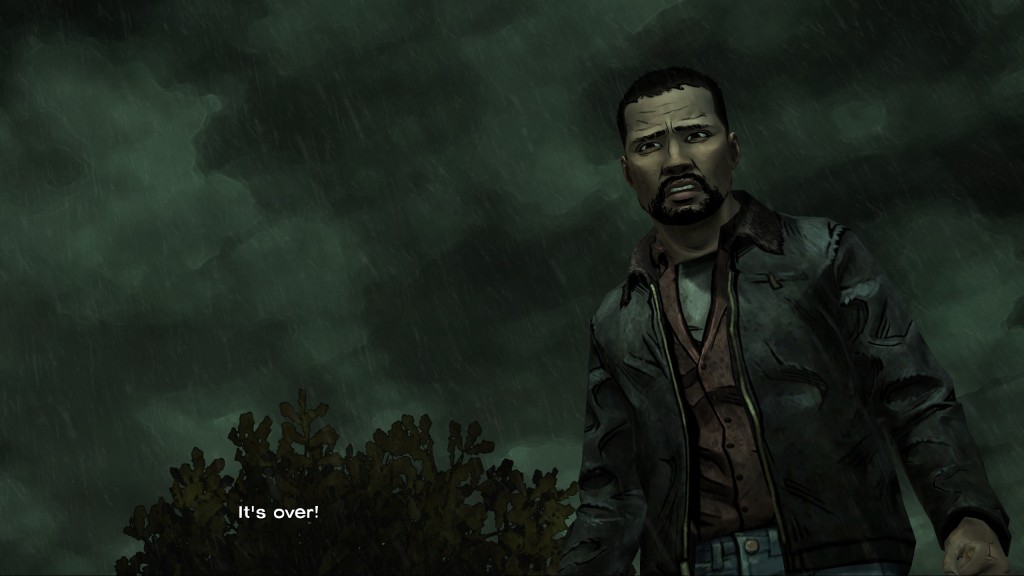

Lee: “It’s over!” Well, for whoever he’s talking to, it is.

But those are just two tiny flaws on the face of what is, let’s face it, one of the best games of this year. In the grand scheme of things, The Walking Dead isn’t just any point-and-click interactive adventure story, it’s the point-and-click adventure game of the year. Games such as DayZ and the recently-released Guild Wars 2 require you to pour a significant number of hours into the game before you start getting anywhere, whereas The Walking Dead is eminently casual. There’s arguably as many cut-scenes as there is actual gameplay, so if you’re not into the whole story aspect, then this might not be a great fit.

At the end of the day, there is no higher recommendation I can make for you to play The Walking Dead by Telltale Games. It features compelling gameplay with real, believable characters and some of the worst decisions you’ll ever have to make in a video game, but it’s also one of the best zombie apocalypse experiences you’ll ever have (as far as “good” zombie apocalypses go, but you know what I mean). It’s available on pretty much every major gaming platform, and you would be doing yourself a disservice by not playing it. Telltale Games have released one of their best titles yet, and with only three of five episodes released thus far, there’s still plenty of the game left to come.

I can’t wait.